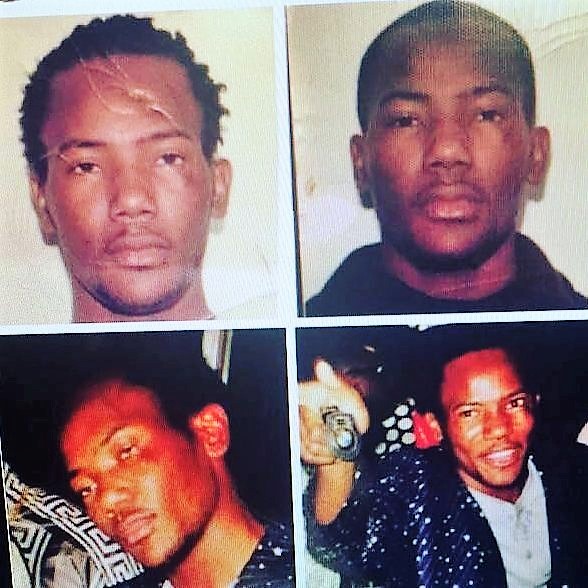

Award winning Jamaican reggae music producer Ralston “Tru Blue” Wellington died on 27 October 2017. I reflect here on the two years I spent living in prison next to the cell of a man I knew as Bilal The Jamaican.

I was walking along the corridors of HM Prison Belmarsh back to House Block 4, at the end of a prison visit. I found myself walking next to another prisoner.

“I’m Bilal,” he said with a warm smile and a strong Jamaican accent, as we shook hands and exchanged salams, the Muslim greeting of peace.

“They also call me Blue.”

Bilal was of similar age to me, 31 at the time. He was tall, slim, with a pronounced forehead and a prominent scar under his left eye.

It was April 2005. I had been in prison for 8 months without trial fighting extradition to the United States.

“I’ve been in prison since January 2003,” Bilal told me. “I’m also fighting extradition to the US.”

Bilal had converted to Islam soon after arriving in Belmarsh. There was a good Muslim community in Belmarsh at the time, and many prisoners were converting to Islam.

Some were converting sincerely, others were converting for company, protection, or to sell drugs at Friday Prayers.

Bilal, whose real name was Ralston Wellington, was being sought by the US State of Missouri accused of a drugs-related double murder in Kansas City in 1997.

A few moments later, I again shook hands with Bilal as we parted company to go to our respective House Blocks.

Days later I was transferred out of Belmarsh to another prison.

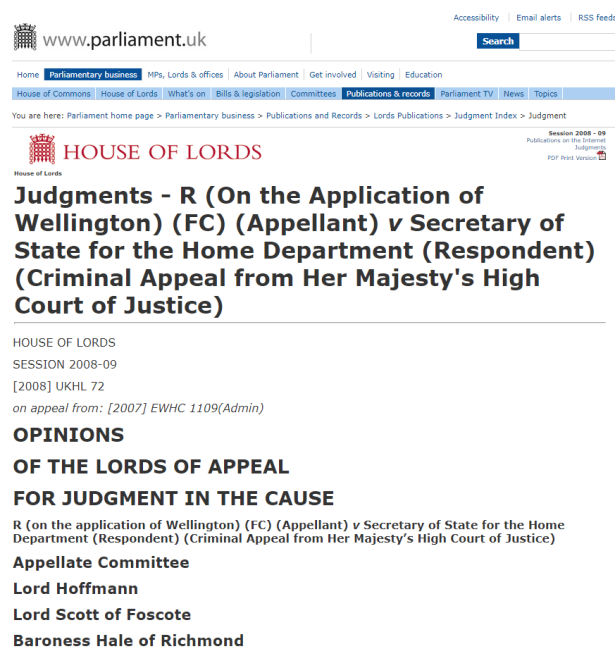

Over the years to come I would read the words United States v Ralston Wellington many times in legal papers and hear it mentioned by my lawyers.

“Wellington” was the most prominent US extradition case going through the UK courts.

Three years passed. By 2008 I was one of only five detainees left on the Detainee Unit in HM Prison Long Lartin.

All the other Muslim detainees facing deportation or extradition had either been released on bail, or extradited.

One day a new prisoner came onto our unit. It was Bilal. We hugged and exchanged salams.

Two of the detainees already knew Bilal well as they had lived with him for years in Belmarsh.

Bilal was not in prison for terrorism allegations, but he was a Muslim detainee held without trial facing extradition to another country.

As Bilal sat down to tell us his story, it transpired that the Prison Service was also struggling to house Bilal as he had been involved in several violent incidents around the prison system.

He had been accused of fighting with other prisoners and as a result he was being moved from segregation unit to segregation unit around the eight high security prisons in the UK.

Bilal moved into the cell next to me and very quickly settled into the calm and laid back life on the Detainee Unit.

He was very different to when I had met him in Belmarsh three years earlier.

The Bilal infront of me had a beard, could read Arabic and was clearly now a devout Muslim.

Prisoners who spend a lot of time in segregation units tend to become more devout as they have more time to read and reflect.

When you have no company except your own soul, you begin to see what is wrong in your life and try to correct it.

Bilal was a colourful character. Living with him immersed me into Jamaican culture.

Bilal wasn’t a British Jamaican like many black prisoners in the UK, he was a Jamaican Jamaican.

He used to tell me stories of his childhood in Jamaica, the poverty, the drugs wars between different areas (“garrisons”), the violence.

Along with the morbid stories were the stories of the island, its fruits and its cuisine. Like most Jamaicans, Bilal was a very good cook.

He was also very generous and would always share his food with other detainees.

Sometimes we would all share to buy ingredients for him to cook, other times he would share from what he had bought and cooked himself.

Fried plantain, peanut porridge, jerk chicken, curried goat (lamb because halal goat meat was not available on the prison canteen), corn, sweet potato pudding, dumplings…

My favourite was the cornmeal porridge: a delicious breakfast meal of cornmeal, creamed coconut, cinnamon and brown sugar. I could eat bowls of that in one sitting.

Bilal knew that I liked cornmeal porridge so he would always make some extra to give to me. With time, I learned from Bilal how to cook some of these dishes myself.

I also learned from Bilal how to understand the patois English dialect spoken in Jamaica as well as Jamaican street and prison slang.

I would shock and impress other Jamaican prisoners with my newly found language skills to much laughter.

Bilal shared my mischievous sense of humour. Together we would play pranks on prison officers and other detainees when the opportunity arose.

In his previous life Bilal had been a popular music producer in Jamaica, known by his label name “Tru Blue.”

That’s where his prison nickname, “Blue” came from. Though there were many Bilals in the UK prison system at the time, there was only one Blue.

But by the time Bilal arrived at Long Lartin in the middle of 2008, he was very much a devout Muslim.

He was praying five times a day, reading Islamic books, performing extra voluntary fasts.

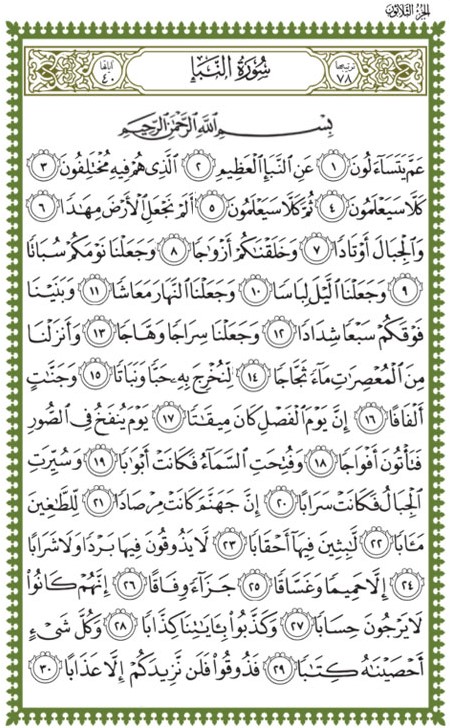

He was also very much attached to the Quran. He had a large Arabic copy of the Quran.

Every few weeks he would ask the officers to photocopy some pages from it, paying 10p per page from his prisoner money account, then he would hang up the sheet on his curtain and pray while reciting from the sheet.

In this way he was able to memorise word for word the entire 30th juz (section) of the Quran, totalling some 20 Arabic pages.

Upon his request, I sat with him over several weeks and taught him tajweed, the science of reciting the Quran with correct pronunciation.

At times I would be busy in my own affairs but he would pester me for the lesson.

“Babar, you don’t have any time for me today, my brother?” he would tease me.

In the evenings after lockup I would hear Bilal through the thin wall that divided our cells, reciting the Quran for hours and hours.

Sometimes he would stop at a mistake, then repeat that verse again and again until he got it right.

“Whatever his issues, this man loves the Quran,” one detainee once said to me about Bilal.

It was apparent though that Bilal had a troubled childhood. His past would sometimes show in his character and lead to conflicts with the other detainees, including myself.

But this man, who had allegedly been involved in murders and stabbings outside and inside prison never once raised his hand at any of the Muslim detainees.

I saw him livid with anger on many occasions. But not once did he ever raise his hand at any of the Muslim detainees.

And whenever he would be wrong, he would always apologise. “I’m bipolar,” he would often say.

Once Bilal had a dispute with one of the detainees and the two stopped talking to each other for about two weeks.

One day after the detainees prayed, Bilal stood up and announced to the other detainees: “I would like to apologise for my behaviour over the last two weeks and especially to my brother …”

He then kissed that detainee on the head and said, “I love you for the sake of Allah.” Under the troubled man was a good heart and it was that heart that I saw.

Bilal was in conflict with several Jamaican and black prisoners in the UK prison system, some of whom had since accepted Islam.

Through talking and listening to both parties, with the Grace of Allah I was able to help Bilal resolve these conflicts.

Two years later, by 2010, there had been some developments in Bilal’s case in the US.

Prosecutors had offered a plea deal to Bilal’s co-defendant: a low sentence in exchange for a guilty plea on lesser charges.

Bilal made contact with a lawyer in the US and then he began to make arrangements to agree to be extradited to the US.

One morning in September 2010, all the detainees were moved to another prison while renovation work was carried out on the Detainee Unit. Except Bilal.

As I packed my bags and left my cell, I opened the flap covering his door window. “All the best, my brother,” I told him.

“Keep good company and don’t ever forget your salah (prayer) and Quran wherever you go. May Allah be with you.”

As he smiled and greeted me back, he said, “May Allah bring you home to your family quickly, my brother.”

A few months later, I received a postcard in my prison mail. It was from Bilal.

He was in a state prison in Missouri, awaiting to be sentenced after pleading guilty to manslaughter.

Another few months passed, and I received another postcard.

Bilal had received a sentence of 15 years which meant that, with credit for time served, he would be released in three years time, in 2014.

That was the last I heard from Bilal.

I was extradited to the US myself in 2012 and I was released and returned home to the UK in 2015. Four months after my return I began to write a book about my experience.

A few weeks ago I was writing about life in the Detainee Unit when I began to write about Bilal.

“Let me google him,” I thought to myself, “to see what he is up to you and maybe reestablish contact with him.”

I entered the words, “Ralston Wellington” into the search bar and clicked enter. The results came up. My heart sank.

“Still no motive in music producer Tru Blue’s killing | News | Jamaica” the headline read.

Bilal had been shot dead in his home in Kingston, Jamaica, on Friday 27 October 2017.

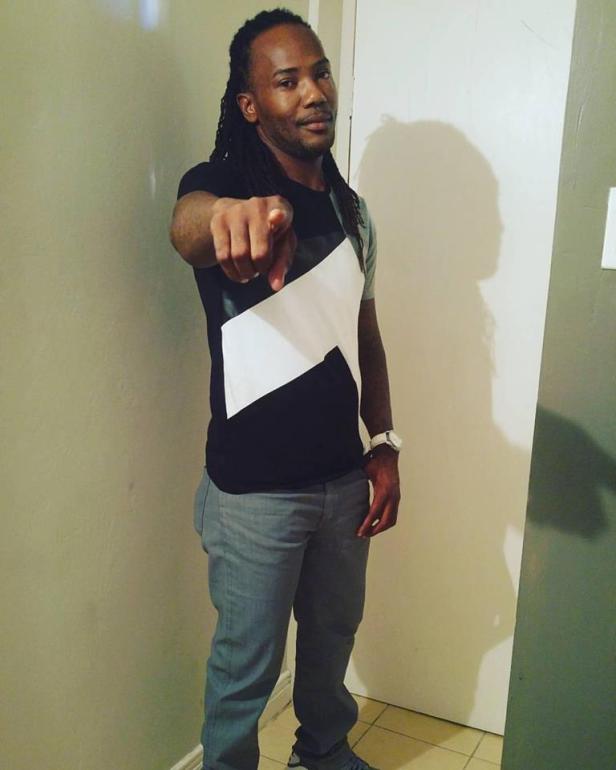

I immediately began to research into his life before he was killed. I found his social media pages.

Bilal had returned to his life as a music producer. I found photographs of Bilal in parties and clubs, surrounded by scantily clad women.

There was a photograph of him holding a copy of an award that he had won.

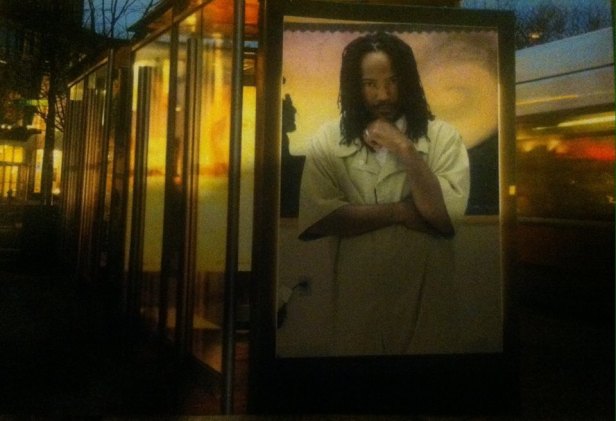

A photograph of Bilal on a poster at a bus stop in Jamaica.

My mind flashed back to the voice reciting Quran in the cell next to me. My only concern at this stage was whether Bilal died as a Muslim.

No-one is perfect but as long as he died as a Muslim then I could rest assured that he would eventually be OK in the Hereafter.

I continued my frantic search through his social media profile.

I found a photograph of an album that he had released, called Ghurabaa, after his favourite Islamic nasheed that he would listen to and sing while working out in the Detainee Unit gym.

I chuckled to myself, wondering what the writer of the Ghurabaa nasheed would think if he found out his nasheed was now also the name of a Jamaican reggae album.

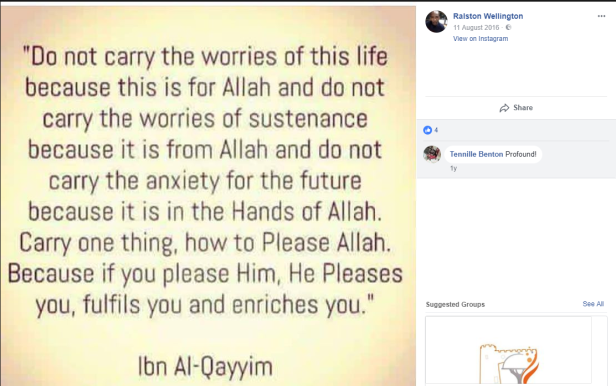

Then there was a quote by a Muslim scholar, Ibn Al-Qayyim:

And then a photograph of Bilal in a mosque, clearly in Jamaica:

I was getting closer, but there was still no conclusive proof that he had died as a Muslim.

Some reports were saying he was killed because of a video message that he had released on YouTube mocking a rival music artist.

Jamaican music figures frequently settled scores through YouTube videos.

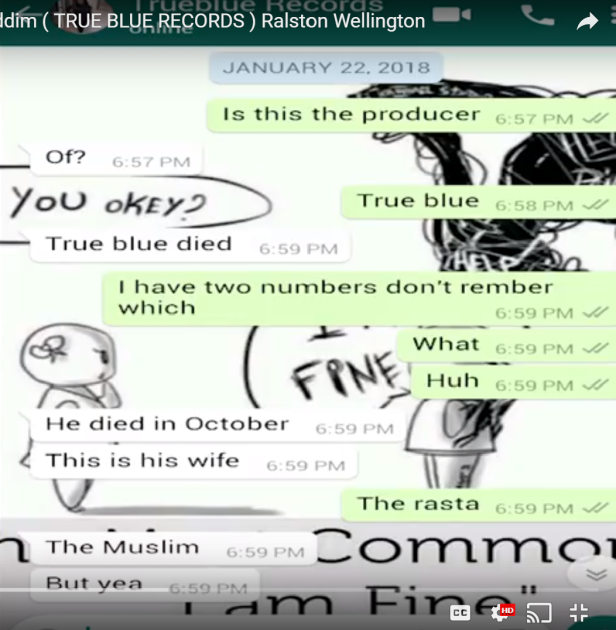

I then found a video which had a screenshot from a Whatsapp thread on Bilal’s phone. Someone wanted to verify what had happened to Bilal.

They asked if this was the number of True Blue. Someone, apparently his wife, replied that True Blue died in October.

“The rasta?” the texter asked to try and confirm.

“The Muslim,” Bilal’s wife replied.

This was a breakthrough. Bilal’s wife, not a Muslim herself, had apparently confirmed that Bilal was publicly known by the local Jamaican music scene as a Muslim, not a rasta.

This was good news, but not good enough.

After several more hours online, I tracked down Bilal’s sister and daughter, and sent them messages. I introduced myself and my relationship to Bilal.

Bilal’s daughter replied. She was a model, working and living in London. She herself was not a Muslim.

She remembered me from when she used to come and visit Bilal at HM Prison Long Lartin.

I would be sitting with my family in the visits hall when Bilal’s daughter, then a ten year old girl, would come to visit him.

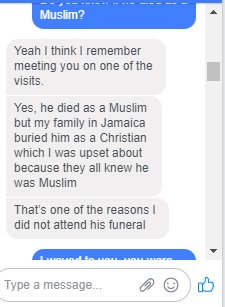

After passing my condolences I asked her the million dollar question. “Did he die as a Muslim?”

“Yes,” she replied. “He died as a Muslim but my family in Jamaica buried him as a Christian which I was upset about because they all knew he was Muslim.”

I breathed a sigh of relief.

“It doesn’t matter how they buried him,” I replied to his daughter. “God knows he died as a Muslim.”

And then, just the other day, I found a notice that Kingston Central Mosque performed a Muslim janazah prayer for him on Friday 15 December 2017.

So he definitely died as a Muslim.

The Prophet (pbuh) once gave a parable of good and bad company.

Good company was like a man who visits a perfume seller. “Even if you don’t buy some of the perfume or apply it to your body, you still leave his shop smelling nice.”

And bad company was like a man who visits a blacksmith. “Even if you don’t bellow the iron with him, you will still come away covered in and smelling of soot.

Company clearly has an effect on people. This could not have been more evident in Bilal’s case.

Whatever his deeds, at least he was not a rat. At least he did not give false testimony against anyone just to save himself.

Reflecting on Bilal’s life, I realised that there is good and bad in all people. Only the ratios differ.

But it is for Allah to judge people. Not us.

May Allah forgive Bilal, have mercy on him and reunite him with the Muslims in the Hereafter.

My story and why I was in prison can be read here.

Sign up in the mailing list form below to receive my blog posts by email.

JazakAllah khairraan please is Thisbe Brother Baba Ahmad who was extradited to America? Or you back into England as I have always have you in my dua.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes this is me. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks man, that was my father

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’m so sorry to hear of your loss. As Muslims we believe that one of the ways children can benefit their fathers after their deaths is by worshiping Allah and praying to Allah for their fathers.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Subhanallah what a journey, may Allah grant him forgiveness & jannah.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes ameen

LikeLiked by 2 people

Such an emotional story. May Allah forgive Bilal for his shortcomings, accept his good deeds and grant him Jannat – ul – Firdous. This is the Night of Power. May Allah lighten his grave and forgive our borther, Bilal. 😥

LikeLiked by 3 people

Amin

LikeLiked by 2 people

JazakAllah for sharing, brother. It’s also a timely reminder about environment and company, given the end of Ramadaan and the not so good habits some Muslims may return to.

It also reinforces the lessons of how every saint has a past, and every sinner has a future. Only Allah knows how we’ll meet our end, and whether that will be in a condition of Islam or not.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Br. I have read your attribution to BILAL the Jamaican Muslim music producer. I am also a Jamaican x=musician being a Muslim for 43 years living in London and an Author whose books can be vued on http://www.Amazon.com . My latest Book The Hijackers by sheikh kamaludin website http://www.gatewaytoilm.com. Do get in touch

LikeLiked by 2 people

I am also an Author Muslim Jamaican x=musician do get in touch

LikeLiked by 3 people

Allah grant him forgiveness and mercy. Ameen…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great story bro !

LikeLiked by 1 person

I met him before, he was one of my mentors as a upcoming musician at the mixing lab , roy studio in kingston. I was telling him that i wanted tatoos on my arms very much like his and he smiled and said “oh really , suh u a gwaan” he taught me alot about music and thats how i met aicha jacas once and she gave me some excellent pointers, maybe she dont remember me but i do. His passing was tragic, when i came to studio and was told that be died and how be died its unbelieveable, i eventually stoped doing music. Its funny how it still impacted me to this day in ways that i cant describe because he was more than a mentor to young artiste, hes a true friend.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing, yes his passing was tragic 😞

LikeLike

This story was wonderful, that was my dad 💕

LikeLike

I thank you💙🤞🏿

LikeLike